On Saturday, October 12, hundreds of demonstrators marched in downtown Montreal in support of the 10-year-old boy who was allegedly scalded on October 2 by one of his neighbours, Stéphanie Borel. This event has rekindled concerns in the community, which is increasingly questioning the safety of its children. La Converse went there to understand their concern.

It's a story that seems to be repeating itself. On October 2, a 10-year-old black child suffered severe burns to his upper body. Stéphanie Borel, a neighbour living in a building near the intersection of Boulevard Curé-Poirier Est and Chemin de Chambly in Longueuil, allegedly threw boiling water at the child simply because he stepped on her land. The young boy told Radio-Canada that he was coming home from school with friends and that they had taken a shortcut, passing in front of Stéphanie Borel's residence. The child suffered second degree burns to his body and face. On the same day, Stéphanie Borel, 46, was arrested and then released.

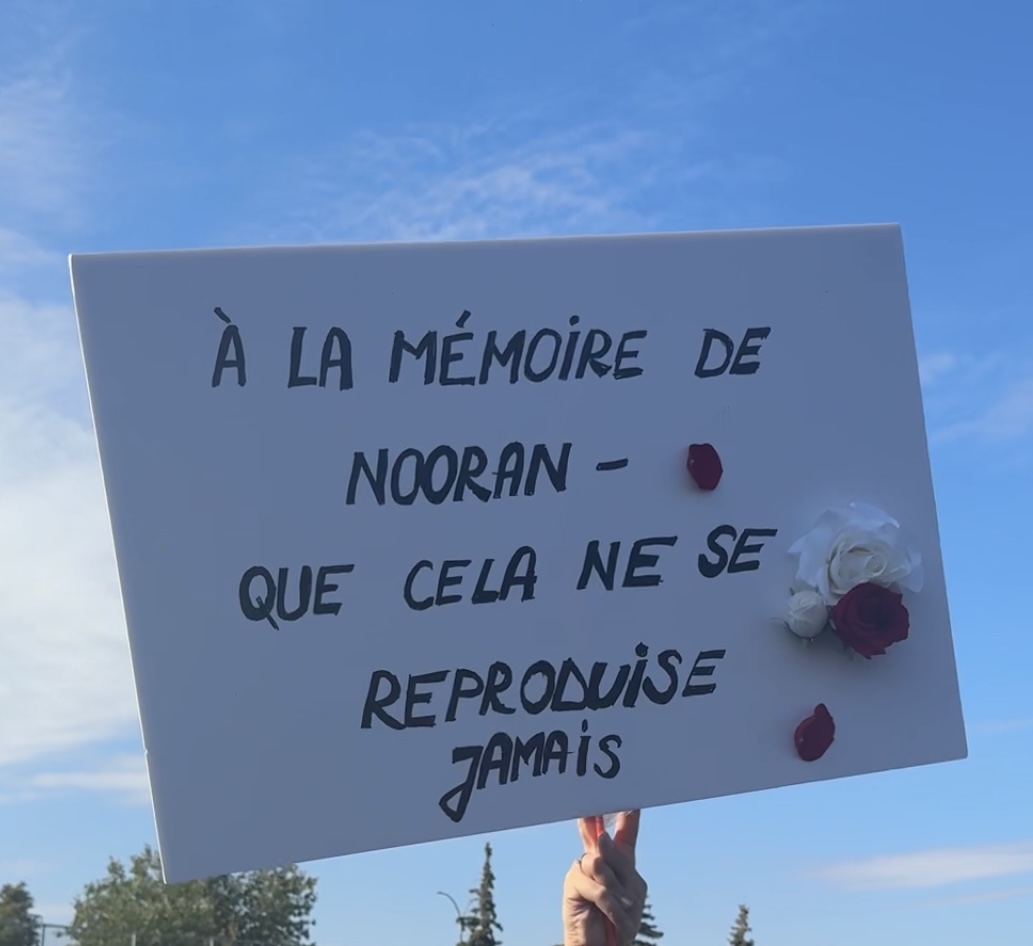

This tragedy was the last straw for the black community, since a few months earlier, in July, a two-year-old girl also suffered severe burns after a day in a daycare in Montreal, an incident that had already shaken the community.

In response to these cases of attack and abuse, on October 12, a peaceful march was organized by the African Federation and Associations of Canada (FAAC) in collaboration with La Ligue des Noirs de Québec (LNQ). This event brought the community and its allies together, not only to support the little boy but also to demand justice.

“We want equality and we want it yesterday! ”

The appointment is set at Place Émilie-Gamelin at 2 p.m. A hundred demonstrators are gathered. They hold up signs and flags in the colors of several African countries. As the march began, slogans echoed in the streets of Montreal: “A fairer and safer Quebec for our children,” “Justice for our children.” “Down with racism! Down with injustice! ”

After the incident, Stéphanie Borel allegedly explained to the little boy's father that she had acted that way because the young child had been in the habit of knocking on her door for three years. A story that the father contested because the family only moved to the neighbourhood in January and the boy started attending school near the woman's home only a month ago.

Although Stéphanie Borel was initially arrested by the police, she was released the same day in exchange for a promise to appear in court next January. A decision that aroused outrage in the community.

“If it had been a Black woman who had scalded a white child, things would have turned out a lot differently, and we all know that! ”, several demonstrators are outraged.

On Place du Canada, the finish point of the march, Mr. Stanley Bazin, president of the LNQ, spoke: “We want justice. We don't want to go looking for it, or beg for it, he starts. We want equality, and we want it by yesterday!”

In the middle of the crowd, we meet Evelyne François, a protester who simply presents herself as “a citizen but also a mother.” She is holding a sign that reads: “We are stigmatizing our black children.” She protests: “we are humans! We want to assert our rights! So we have to stand up for justice.” She continues: “This woman deliberately prepared hot water to burn this child. A 10-year-old child who did nothing to deserve this! And yet, this 'criminal' was released pending trial? How is that possible? Where are we going? What world do we live in?”

In this context, the Red coalition, a pressure group that fights against racism, wrote a letter last Thursday to the attention of the mayor of Longueuil, Catherine Fournier, and to the police chief Marc Leduc, asking that Stéphanie Borel be detained again. The same day, the Mayor of Longueuil mentioned in a statement published on social networks that it was very rare for all legal criteria to be met to justify the detention of a suspect even before the start of the investigation. “Since yesterday, several people have been calling on me personally on this subject, urging me to act to reverse the situation (...) I could never, as an elected official, ask to review a police or judicial decision, let alone demand a review of a police or judicial decision, let alone demand the detention of a person. That would be illegal.”

Rolande Balma, municipal councillor for the Antoinette-Robidoux district, where the little boy lives, also spoke at a Longueuil city council meeting: “no child and no parent should experience such an awful situation. Of course, the investigation is ongoing, we will let justice decide. But I won't hide the fact that I shed tears when I saw this child's skin.”

The next day, Friday October 11, Stéphanie Borel was arrested again “following the obtaining of new elements of the investigation” against her, explains the Longueuil Agglomération Police Department in a press release. She has been "formally charged with aggravated assault and will remain incarcerated“, indicates Radio-Canada. a more serious charge than the counts of assault with injury and armed assault that were originally filed. She is expected to remain incarcerated at least until October 28.

A hate crime?

Back in Place du Canada, several demonstrators denounce a hate crime against children. But according to the law, what really characterizes such an act and how do you prove it? That's the question we asked Fo Niemi, co-founder and executive director of the Center for Research-Action on Race Relations (CRARR) dedicated to the defense of civil rights.

“According to the Canadian Criminal Code, a hate crime is an offence motivated by hatred of race, religion, gender, or other protected characteristics. If such motivation is proven, it becomes an aggravating factor that increases the sentence," Niemi begins. "However, without solid proof of this motivation, the act will not be qualified as a hate crime, thus limiting the severity of the penalty.”

This proof of motivation is often difficult to demonstrate, says Niemi. “This is what we have seen in several cases over the last 10 years: the Crown does not always raise this aspect,” he explains. Even if there is evidence of hateful motivation, proving this intent remains a major obstacle in criminal trials. “You really need to look at what was the motivation of the person who committed the act,” Niemi insists, stressing that this burden falls on the Crown.

In 2023, Statistics Canada registered a total of 784 complaints of hate crimes reported by police against the Black community in the country. Despite a decrease of 7 per cent compared to the previous year, it should be noted that hate crimes against Black people in Canada jumped by 96 per cent between 2019 and 2020.

The Black community remains the most affected by hate crimes in the race and ethnicity category.

Solidarity in pain

Anastasia Marcelin, a member of the LNQ, in turn, speaks out on Canada's place: “It is time to put an end to our divisions. If you don't wake up now, your children will continue to fight for their rights! ” she launched forcefully. Her voice echoed in the square. She continued: “In 2020, we were here to say Black Lives Matter. Today we are back because our children are getting burned! If we remain inactive, the situation will only get worse. We risk an escalation of violence.” She points to a protester in the crowd: “If you don't move, it's the children who will still have to fight.” The crowd, united, answers in chorus: “solidarity, solidarity! ”

In this momentum of unity that has brought together several Black communities, a second march is planned on Saturday, October 26 at 2 p.m., with a departure from Place Émilie-Gamelin, announced the FAAC spokesperson.

To go further:

The Centre de prévention de la radicalisation menant à la violence offers tailored support for victims, witnesses or actors of hate crimes and incidents.