With just a few days to go before the election, one question is on everyone's mind in Montreal North, Saint-Michel, and Côte-des-Neiges: why vote in the federal election if nothing changes in my neighborhood? In these neighborhoods, which are often plagued by poverty, insecurity, and a sense of abandonment, voter fatigue is palpable. For many, voting is not a promise of a better future, but simply a duty, a gesture made out of principle. Behind this weariness, confusion surrounding the different jurisdictions of government levels muddies the waters and increases disengagement. However, voices are being raised, voices that are well known in their neighborhoods. Municipal officials, researchers, and ordinary citizens are working to rebuild the links between politics and the people. Report.

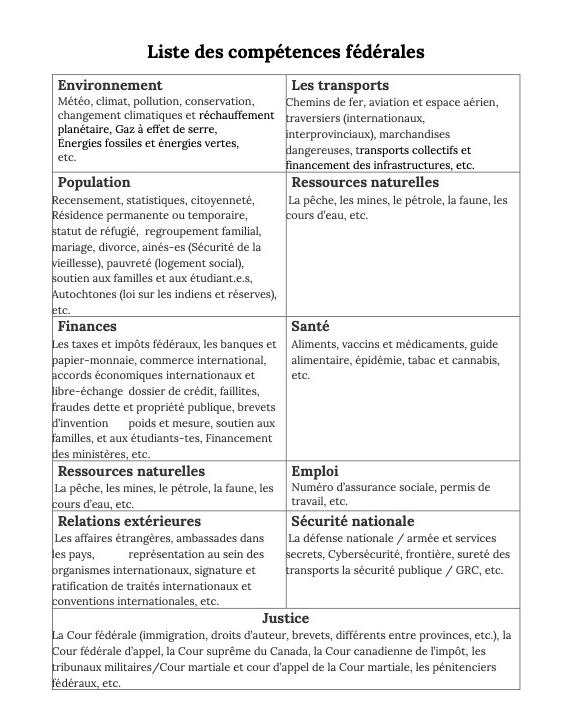

Thursday, April 10. After a vox pop at the Pretty Little Thing nail salon, we interview a passerby in the Saint-Michel neighborhood. Although she is clearly in a hurry, she stops and takes the time to share her concerns with us as the federal election approaches. “What bothers me are the bike lanes! Here in Saint-Michel, everything is far away, and yet they want to prevent us from using our cars. Public transportation isn't always the best solution.” With two weeks to go before the election, this isn't the first time we've heard this comment, which reveals the confusion that reigns between municipal, provincial, and federal jurisdictions. We explain to her that bike lanes are the responsibility of the City, not Ottawa. She stares into space: “Oh... Really? Well, I don't know who I'm going to vote for yet, but I'm going to vote.”

This exchange speaks volumes about the sense of distance from federal politics felt by many voters in Montreal's more outlying neighborhoods.

“There is a lot of confusion between the roles of municipal, provincial and federal government.”

Stéphanie Valenzuela, city councilor for the Côte-des-Neiges–Notre-Dame-de-Grâce borough in Montreal, understands well the sense of distance that many voters feel toward the federal government. For several weeks, she has been walking the streets of her district, knocking on doors and encouraging citizens to exercise their right to vote—an effort she is undertaking in a non-partisan manner. We caught up with her via videoconference on the first day of advance voting.

“Citizens aren't disinterested, they're confused,” she begins. ‘There's a lot of confusion about the roles of municipal, provincial, and federal governments.’ This confusion, she believes, undermines civic engagement.

In a neighborhood like Côte-des-Neiges, where the majority of residents are immigrants, this confusion often translates into a lack of reference points, she continues. “People contact me about issues that are not within my jurisdiction. Often, it's just that they don't have a point of contact; they don't know where to look.”

She then becomes that point of departure. “Even if it's a question about immigration or health issues—which are not municipal matters—I take the time to listen to them, guide them, and direct them to the right resource.” It is through these small gestures, she says, that bonds of trust are formed.

“When someone realizes that you've helped them once, they come back. And sometimes they send their neighbor, their cousin, their mother... That's how you create a support network in the neighborhood and how you're able to better meet people's needs.”

The federal level, she continues, is often perceived as being the furthest removed from citizens. Yet without it, many projects would struggle to get off the ground, as municipal and provincial governments often depend on its support.

She cites the example of the Namur–Hippodrome neighborhood, a large urban redevelopment project in her borough. “This project perfectly illustrates the complexity of shared responsibilities. The federal government funds the construction of social and affordable housing; the provincial government redistributes the funds; and the city develops the land. But the concrete results are slow in coming.”

And then there are the deadlines, the red tape, and the decision-making channels that don't communicate with each other. Ms. Valenzuela explains: “In Quebec, it's even more complicated. Unlike in other provinces, the federal government can't fund municipalities directly. The money goes through the provincial government, which then decides how to allocate it. So it takes time. And when people don't see results, they give up.”

She sees this feeling of powerlessness every day on the ground. “People say to me, ‘We vote, but nothing changes,’ but I insist on making people understand that abstention is not a solution. If you don't vote, someone else will decide for you. And that person may not have the same priorities as you,” she says with a shrug.

Her convictions sometimes push the city councilor to go beyond her formal role as an elected official. ”It's not officially part of my job, but I've already accompanied residents to the federal polling station. Because they didn't know how to get there. Because they weren't sure what to bring. Because they needed support in the process,” she says.

“It's not normal for people to be so confused. We have to give them the keys, explain the issues, and make the information digestible. Not everyone has the time or ability to read election platforms or attend debates. We can't expect that level of engagement when living conditions themselves make it difficult,“ concluded the city councilor.

”The standard citizen we address in all political discourse is the white middle class."

Céline Bellot, a professor at the University of Montreal's School of Social Work, argues that the supposed disinterest of people from working-class or marginalized groups is “a myth that needs to be debunked.”

She does not question the political engagement of these people, but rather points to the systemic barriers that hinder their participation.

She denounces an electoral system designed for an “average” voter who is far from representative of Canada's diversity. “The standard citizen addressed in all political discourse is the white middle class. Even if it's not explicitly stated, that's what the programs are based on. We're talking to a white majority,” she says bluntly.

In this context, racialized, Indigenous, homeless, and disabled people are excluded from a political narrative that does not recognize them. “As soon as you step outside the framework of the average citizen—someone who is settled, has transportation, and shows an ‘acceptable’ interest in politics—you face barriers to access. And sometimes a form of disengagement, but this is mainly a reaction to exclusion.”

This phenomenon is also evident in Indigenous communities, with whom Ms. Bellot works closely. “We see a real disconnect between participation in a federal system and demands for autonomy or self-determination,” she explains. Clearly, there's a clash. It's not disengagement, it's a clear demand: this is not the framework in which these communities want to engage politically.”

Ms. Bellot insists that we must stop believing that voting is the only valid expression of political engagement. “You can take all kinds of action [volunteering, demonstrations, collectives, civic engagement] and make political commitments that we won't consider political engagement because you're not in a traditional party or a youth member of a political movement. What we expect is that everyone plays the same game, but the rules of that game are not the same for everyone.”

And even in the rare cases where political parties do reach out to minority groups—in certain ridings where these groups become electorally significant—it remains a one-off, circumstantial strategy. “The dominant political discourse is still aimed at middle-class Canadians or Quebecers who are not part of minority groups,” she insists.

According to the researcher, political discourse is indeed aimed at the middle class. “It's mentioned in particular to say that taxes will be lowered, and almost all political promises are directed at this group—without it being very clear what the ‘middle class’ actually is,” she adds.

“And why white?” she continues. ”Because we hear very little about racism and racial discrimination. It's not part of the promises, in general. It's simply because we're not addressing a population that has these difficulties or these problems.”

And in this election period, where immigration issues have long been a hot topic of debate, the expert is concerned about another phenomenon: “I'm not convinced that immigrants, even once they become citizens, want to participate in this political game. Not in this context, not with this rhetoric that associates immigration with all kinds of structural failures, particularly the housing crisis, public services, etc.”

Abdelhaq Sari – “What changes things is when people get to know you for who you really are. Not just during a campaign.”

On the ground, you can sometimes feel this tension between the exclusion felt by some citizens and the candidates' desire to take action.

Montréal-Nord. We meet in front of the campaign office of Abdelhaq Sari, Liberal candidate in the Bourassa riding. The place is bright, the bay window covered with posters bearing his photo. The campaign manager welcomes us while two volunteers in their sixties, both on the phone, provide information to voters. One, Maghrébine, wears a hijab. The other, Blanche, speaks in hesitant Spanish: “Sí, pueden votar ya, del 18 al 21,” while her colleague echoes, “Yes, you can already vote in advance starting today.”

The candidate is absent at the moment, we are told. He has gone to visit a polling station, but should be back soon. Fifteen minutes later, a voice calls out: “Ah, the boss is here!” Through the bay window, we can see him: brown suit, broad smile, and an almost presidential wave to a car honking as it passes by. Abdelhaq Sari enters the premises.

On this first day of early voting, he is visibly satisfied. “This morning, I received a lot of calls from people who went to vote. They waited 40 minutes, sometimes an hour. It was really busy!” The turnout motivates him: “It doesn't slow us down. We keep calling, keep mobilizing.”

A city councilor in Montreal North for eight years, the Liberal candidate says he wants to expand his influence at the federal level. “I have people's trust, I have experience, and I want to defend their interests in Ottawa. The issues are there: housing, immigration, the cost of living.”

But he is under no illusions: convincing people remains a challenge. Some people tell him that voting is pointless or that politicians are all corrupt... “If you believe that nothing will change, then stay out of the process. But don't come asking your elected officials for answers,” he says bluntly. He pauses. “The truth is, if you don't participate in the process, you can't expect to influence politics. Protests don't do much good, in my opinion. On the other hand, people who work within the system really have an impact that matters,” he asserts.

The candidate also speaks of a certain confusion among voters: ”Many people don't know the difference between the levels of government. Who does what? It's unclear.” For him, the answer lies in civic education and consistency: “What makes a difference is when people know you for who you really are. Not just during a campaign. When you've been there for them, they remember.”

He talks about lectures he has given in community centers and his discussions with young people about violence and crime. For him, it is these concrete actions, far from the spotlight, that build trust. And that trust, he says, is all the stronger in a neighborhood like Bourassa, where voters can identify with him. “Yes, I am an elected official, but above all, I am someone from their community, I am North African. Someone who understands them. That makes all the difference.”

He says that the citizens in his district are concerned about international conflicts: the situation in Gaza, the war in Ukraine, tensions in Lebanon, and the turmoil in Sudan. “People are asking themselves, ‘What is the position of my elected representative? Of the party? Of the government?’ We have to give them clear answers.” He points out that a motion on the situation in Gaza, which he presented to the city council, was adopted unanimously. “We wanted to send a message of dialogue and respect between communities.”

He has to rush off: another campaign event awaits him five minutes from the office. We accompany him.

Once there, he is quickly surrounded by familiar faces. A family of Moroccan origin approaches him, clearly happy to see him. “We took advantage of the day off to come and vote!” says the father.

One of his children is not old enough to vote, but his father insisted that he attend. “He was playing video games, so I said, ‘Come on, let's go!’”

He continues proudly, ”Ever since we've had the right to vote in Canada, we've done so. It's our duty to choose who will represent us.” To support his cause, he even volunteered as a driver during Abdelhaq Sari's nomination campaign, shuttling his neighbors between their homes and the polling stations. “Mr. Sari doesn't even know,” he says with a laugh. “I'm doing it because he's always been there for us. He's not just a name on a poster. He's someone we really know.”

Marwan El Attar: “We need to shake things up!”

Wednesday, April 23. It's late afternoon in a small Italian café in Saint-Michel when Marwan El Attar, federal candidate for the New Democratic Party (NDP), meets us. With a lively gaze, he sits down with a coffee in his hand. At 32, the lawyer has put his career on hold to avoid any conflict of interest. “I was nominated two days before the campaign started. Since then, I've been running!” And that's not a metaphor. Since the announcement, he has been busy with meetings, visits, and discussions.

Marwan El Attar was born and raised in Saint-Léonard, brought up by a single mother with his two brothers. He does not come from a privileged background. “I grew up in poverty. I understand the issues facing the neighborhood because I have lived them.” It is this direct connection with the community that, in his view, makes all the difference.

“I'm a young man of color from the neighborhood. That reassures [voters]. They see that I understand what they're going through.”

Why run now? “Nothing is changing. We need to shake things up!” He speaks bluntly about the old housing, inadequate transportation, and inflation that is weighing heavily on families. “They always promise that something will be done. But nothing happens. They take us for granted.”

In this neighborhood, voter abstention is nearly 43%. He explains this rate by the residents' inability to plan for the long term: “When you live in a disadvantaged neighborhood, you think first about survival. Not about fulfillment. We forget that we can change things.” So he is betting everything on proximity.

With a handful of volunteers, Marwan criss-crosses the neighborhood. That evening, there is no major door-to-door campaign. Just a few steps down the street, flyers in hand. He spots a passerby, approaches him, and strikes up a conversation. The man seems uncomfortable, nods politely, then walks away. Another, barely addressed, raises his hand and makes a sharp gesture, clearly indicating that he is not interested.

Marwan is not discouraged. “Sometimes it's like that. But other times, it opens a door. All it takes is a conversation. A familiar face.”

He knows that every interaction, however brief, can sow the seeds of doubt, a desire to learn more, perhaps even to vote. He sees himself as a bridge between politics and citizens who are often forgotten. “I live with my wife. And I ask myself, 'If we had children tomorrow, what kind of society would they grow up in? Groceries are already difficult. We can't even afford to buy a house.” Although he is a lawyer, Marwan also feels the economic pressure.

And even if not all the passers-by he meets are receptive, he continues, a stack of flyers in his hand, slowly but surely stirring things up.

La Converse contacted three Conservative Party candidates and three Bloc Québécois candidates to ask if we could follow them on the campaign trail. They were either unavailable or did not respond to our requests.

With just a few days to go before the election, one thing is clear: it is not enough to encourage voter turnout; we must create the conditions for it to become clear to citizens.

FURTHER INFORMATION:

- Voting is no longer possible before April 28, 2025. Find your polling station here.

- Resources in different languages: